the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Extreme lowering of deglacial seawater radiocarbon recorded by both epifaunal and infaunal benthic foraminifera in a wood-dated sediment core

Juan-Carlos Herguera

John R. Southon

For over a decade, oceanographers have debated the interpretation and reliability of sediment microfossil records indicating extremely low seawater radiocarbon (14C) during the last deglaciation – observations that suggest a major disruption in marine carbon cycling coincident with rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Possible flaws in these records include poor age model controls, utilization of mixed infaunal foraminifera species, and bioturbation. We have addressed these concerns using a glacial–interglacial record of epifaunal benthic foraminifera 14C on an ideal sedimentary age model (wood calibrated to atmosphere 14C). Our results affirm – with important caveats – the fidelity of these microfossil archives and confirm previous observations of highly depleted seawater 14C at intermediate depths in the deglacial northeast Pacific.

Given modern carbon cycle perturbations (Keeling, 1960), it is critical to understand the drivers of natural atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) variability. A prime example of this “natural” atmospheric CO2 variability is the increase that occurs at the end of each late Pleistocene ice age (Fig. 1) (Petit et al., 1999). The ocean's ability to store and release CO2 makes it a likely driver of past changes in this important greenhouse gas (Broecker, 1982).

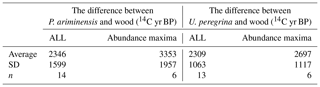

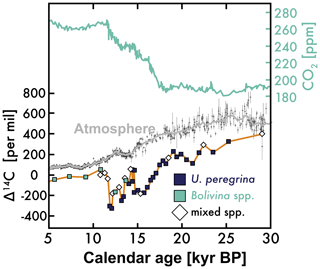

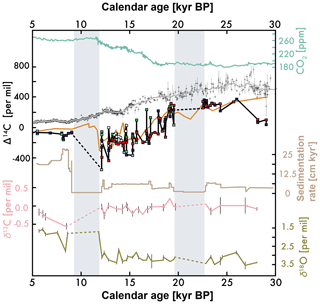

Figure 1Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations (top; blue) (Ahn and Brook, 2014; MacFarling Meure et al., 2006; Marcott and Shakun, 2017; Monnin, 2001), atmospheric Δ14C (middle: blank symbols are observations, gray line is smoothed average) (Reimer et al., 2013), and benthic foraminifera Δ14C from sediment bathed in California Undercurrent water (orange; see Table 1 and maps in Fig. 2) (Lindsay et al., 2015; Marchitto et al., 2007). These observations are shown from 30 to 5 kyr BP (BP: before 1950).

A valuable tool in the effort to characterize the marine carbon cycle over the most recent of these intervals is the 14C content of benthic and planktic foraminifera tests (Broecker et al., 1988), which are assumed to reflect the 14C content of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) in the waters in which they grew. This tracer provides a geochemical “clock” with a predictable decay, but 14C is also affected by a variety of other processes, including the time since the water mass exchanged CO2 with the atmosphere, the degree of this exchange, variations in the atmospheric concentration of 14C at the time of exchange (Fig. 1), and the contribution of 14C-depleted carbon via mixing and/or other carbon sources (e.g., seafloor volcanism; Ronge et al., 2016).

We can relate seawater 14C content to modern ocean conditions by using delta notation or Δ14C (Fig. 1), which corrects for 14C decay.

Equation (1) is multiplied by 1000 to give units of per mil (‰). The 14C calendar age is given in years before 1950 or “before present” (BP).

The available benthic foraminifera Δ14C records paint a complicated picture of glacial to interglacial seawater 14C content. For example, a record of benthic foraminifera Δ14C from the intermediate-depth subtropical eastern North Pacific (Lindsay et al., 2015; Marchitto et al., 2007) shows Δ14C depleted relative to the atmosphere by > 400‰ during the deglaciation (from ≈19 to 11 000 yr BP; see Fig. 1). Later work showed benthic foraminifera with similar or even lower Δ14C values during the deglaciation in other parts of the intermediate-depth ocean (≈500–1000 m), such as the 617 m deep eastern equatorial Pacific (Stott et al., 2009) and the 596–820 m deep Arabian Sea (Bryan et al., 2010). Given that the lowest observed modern intermediate-depth seawater Δ14C is about −300 ‰ (or only ≈300 ‰ lower than the atmosphere) (Key et al., 2004), the low benthic foraminifera Δ14C and old 14C ages suggest much lower Δ14C and older seawater DIC 14C ages during the deglaciation.

A leading explanation for these low-intermediate-depth Δ14C values involves the storage of carbon in an isolated deep-sea reservoir during the glacial period followed by the rapid flushing of this low Δ14C and old 14C aged carbon through the intermediate-depth ocean during the deglaciation – a deep-sea carbon flush that also explains the observed elevation of atmospheric CO2 concentrations and lowering of atmospheric CO2 14C content (Marchitto et al., 2007). This interpretation is qualitatively supported by observations of lower deep-sea dissolved oxygen concentrations before the deglaciation (Jaccard et al., 2016; Jaccard and Galbraith, 2011).

The ocean carbon flushing hypothesis predicts that deep-sea Δ14C during the glacial period will be lower than the extreme Δ14C lowering of the intermediate-depth Δ14C during the deglaciation (Fig. 1) because of mixing with shallower waters with higher Δ14C. However, even though deglacial Δ14C as low as or lower than in Fig. 1 is observed in some deep-sea waters during the glacial period (Sikes et al., 2000; Skinner et al., 2010; Keigwin and Lehman, 2015) and intermediate-depth waters (Burke and Robinson, 2012), it is not clear how these low Δ14C signals are not mixed away en route to the lower latitudes (Hain et al., 2011). Additionally, the lower Δ14C in Fig. 1 is not observed at all intermediate-depth sites during the deglaciation (De Pol-Holz et al., 2010; Rose et al., 2010). Furthermore, the extreme Δ14C lowering observed in intermediate-depth benthic foraminifera during the deglaciation does not appear to be quantitatively consistent with an isolated deep-sea reservoir (Hain et al., 2011).

The inconsistency of the available Δ14C records is compounded by assumptions about the reliability of the foraminifera archive as a recorder of seawater DIC 14C. For example, an important assumption when using planktic foraminifera is that the depth of calcification does not vary based on modern observations (e.g., Field, 2004). The use of benthic foraminifera seemingly circumvents this problem, and those that live at the sediment–water interface (“epifaunal”) have been demonstrated to record seawater carbon chemistry (Keigwin, 2002; Roach et al., 2013). However, the abundance of epifaunal benthic foraminifera is typically low relative to benthic species that abide within the sediment (“infaunal”). Rather than recording seawater 14C content directly, the infaunal species provide a record of sediment pore water carbon chemistry, which may or may not reflect bottom water conditions.

A further complication to published benthic foraminifera Δ14C observations is that both the epifaunal and infaunal species are typically rare in sediments, leading to the common use of mixed benthic species. The mixed-species approach has led, in some rare cases, to anomalously low Δ14C values and old 14C ages through the inclusion of anomalously depleted 14C Pyrgo spp. (Magana et al., 2010) – an anomaly that may not be a global phenomenon (Thornalley et al., 2015). While monospecies epifaunal benthic foraminifera 14C measurements exist (Thornalley et al., 2011, 2015; Voelker et al., 1998), we are unaware of any continuous glacial–interglacial records of monospecies epifaunal foraminifera 14C content. (One study used mixed planispiral species, whose morphology predicts an epifaunal habitat; Galbraith et al., 2007.) An additional influence on benthic foraminifera Δ14C is bioturbation (Keigwin and Guilderson, 2009), which is infrequently quantified, even though it can dramatically affect the observed 14C age (Costa et al., 2018).

The doubts raised by the above complications are amplified by converting the benthic foraminifera 14C age to Δ14C, which requires the user to assign a calendar age to the sediment.

Finally, constraining the age model of sediment cores typically relies upon several assumptions. For example, planktic foraminifera 14C is commonly used to identify the calendar age of sedimentary material, although this requires assumptions about the depth habitat of the planktic foraminifera and the “reservoir age” of the surface waters (the offset between atmosphere and ocean 14C). Other means for determining the calendar age involve tying temporal variability to other paleoclimate and paleoceanographic records (Marchitto et al., 2007; Stott et al., 2009). In rare instances, the 14C of wood from terrestrial plants provides a direct recording of atmospheric 14C, which is well-dated and provides an excellent sedimentary age model (Broecker, 2004; Zhao and Keigwin, 2018), although this work provides some recommendations for utilizing this technique (see below). For our understanding of past and future carbon cycling processes, it is essential that we thoroughly explore these influences and build confidence in these sediment proxy records.

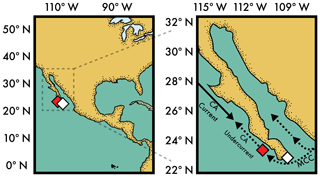

Figure 2Maps of sediment core sites (diamonds; see Table 1) and ocean circulation (solid arrows: surface, dashed arrows: near seafloor). The foraminifera radiocarbon measurements in Fig. 1 are from core sites at the red diamond (Marchitto et al., 2007; Lindsay et al., 2016). See Table 1 for details on site locations. Note that the subsurface Mexican Coastal Current (MCC) flows between 200 and ≈700 m and feeds subsurface water into both the Gulf of California and California Undercurrent (Gómez-Valdivia et al., 2015) – waters that bathe both core sites.

Here, we provide a test of the fidelity of the benthic foraminifera Δ14C proxy using 14C measurements of benthic foraminifera species from two sediment cores near the mouth of the Gulf of California (white diamond in Fig. 2). These sediment cores are unusual in that both epifaunal and infaunal benthic foraminifera microfossils are plentiful and allow us a unique opportunity to test the fidelity of the benthic foraminifera Δ14C proxy. The foraminiferal abundances were quantified to account for bioturbation and the age model is calibrated to the well-constrained atmospheric 14C record (Reimer et al., 2013) via wood found alongside the foraminifera. These cores (from here on, the Gulf sites) allow us to present glacial–interglacial 14C measurements produced from four benthic foraminifera, including the preferred epifaunal species Planulina ariminensis (Keigwin, 2002). The Gulf core sites are bathed in the subsurface northward-flowing Mexican Coastal Current (MCC in Fig. 2), which is the source of the California Undercurrent (Gómez-Valdivia et al., 2015) – waters that also bathe the well-known sites on the Pacific margin of Baja, California, shown in Fig. 1 (from here on, the Undercurrent sites). This shared seawater source gives the expectation of a similar Δ14C signal at both sedimentary locations – an expectation that we exploit to examine the potential for diagenetic alteration of the benthic foraminifera Δ14C observations relative to sedimentation rates, which are significantly lower at the Gulf sites (≈2 to 5 cm kyr−1; our study) relative to the Undercurrent sites (> 25 cm kyr−1; Lindsay et al., 2015; Marchitto et al., 2007) (“kyr” is 1000 years). These and other hydrological, geochemical, and diagenetic influences on benthic foraminifera Δ14C are examined below with the goal of answering an important question: are these benthic foraminifera Δ14C records recording an extreme lowering of seawater Δ14C during the deglaciation?

Sediment from Gulf of California sites LPAZ-21P (22.9∘ N, 109.5∘ W; 625 m) and ET97-7T (22.9∘ N, 109.5∘ W; 640 m) (white diamond in Fig. 2; Table 1) was washed using de-ionized water in a 63 µm sieve. Foraminifera abundance estimates of Planulina ariminensis (benthic; epifaunal species), Uvigerina peregrina (benthic; shallow infaunal species), Trifarina bradyi (benthic; deep infaunal species), mixed Bolivina (benthic; deep infaunal species), and Globigerina bulloides (planktic species) were made after quantitatively dividing the > 150 µm fraction of each sample using a Green Geological aluminum microsplitter. These estimates were made for all samples from core LPAZ-21P and select samples from core ET97-7T. Preliminary work measured the 14C age of mixed benthic species from the ET97-7T core site and although the species abundance was not quantified, they primarily included Planulina spp., Uvigerina spp., and Trifarina spp.

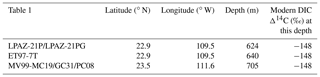

Table 1Latitude, longitude, depth below modern sea surface, and modern dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) Δ14C (26) at the sediment–seawater interface for sediment cores discussed in this study.

2.1 Radiocarbon measurements

Monospecies foraminifera and wood were selected for 14C analysis from the > 150 µm fraction from both gulf sediment cores. Each foraminifera sample was sonicated in methanol (≈1 min) to release detrital carbonates trapped within open microfossil chambers. At least 10 % of each sample was dissolved using HCl to remove secondary calcite (precipitated postdeposition), though in-house tests with and without this pretreatment yielded identical results for these core sites. Wood fragments from the > 150 µm fraction were prepared using standard acid–base–acid treatments.

Samples were graphitized following Santos et al. (2007) and analyzed at the Keck Carbon Cycle Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (KCCAMS) laboratory at the University of California, Irvine (Southon et al., 2004). We report radiocarbon as Δ14C in units of per mil (‰; see Eq. 1 above), which is corrected for decay based on its age normalized to 1950 according to convention (Stuiver and Polach, 1977). Analysis of a sedimentary standard (FIRI-C) alongside measurements indicates a combined sample preparation and measurement 14C age error ranging from ±50 years for a full-size sample (≈0.7 mg of C) to ±500 years for very small samples (< 0.1 mg of C). Because of the similar location of the sites near the mouth of the Gulf of California, we combined the 14C measurements from both cores.

2.2 Oxygen and carbon stable isotopic measurements

The 18O∕16O and 13C∕12C of benthic foraminifera were measured using a Kiel IV carbonate device coupled to a Delta XP isotope ratio mass spectrometer at the University of California, Irvine. Isotopic ratios are reported in delta notation, where δ13C = ( − 1) and δ18O = ( − 1). Each was multiplied by 1000 to give units of per mil. The standard for both measurements is VPDB.

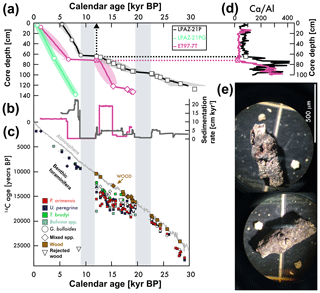

Figure 3(a) Sediment core depth versus calendar age. Age model constraints are based on wood 14C (squares and diamonds), stratigraphic correlation (X; see d), and U. peregrina 14C corrected for reservoir age (circles). (b) Sedimentation rate versus calendar age. (c) The 14C age of atmospheric CO2, foraminifera, wood, and rejected wood (see legend) versus calendar age for ET97-7T (diamonds) and LPAZ-21P/LPAZ-21PG (squares). See Fig. 1 and Table 1 for locations. (d) Ca∕Al for ET97-7T (pink) and LPAZ-21P (black) was measured using X-ray fluorescence (see “Materials and methods” section). Lower Ca∕Al for the uppermost sediment (beginning at the arrows) is coincident with loss of calcium carbonate microfossils and an overall darkening of sediments at these and other sites in the region (van Geen et al., 2003). We use this stratigraphic feature to tie the age model for both sites (dashed arrow between the X symbols). (e) Examples of wood found within sediment core LPAZ-21P (see scale).

2.3 Age model construction for Gulf of California sediment cores

The age model for LPAZ-21P (between 30 000 and 12 100 years BP) is constrained by 13 microscopic wood fragments calibrated to calendar ages using CALIB7.1 (Stuiver et al., 2017) with the IntCal13 atmospheric 14C dataset (Reimer et al., 2013) (squares in Fig. 3a and c). Five wood measurements from LPAZ-21P did not pass our test for use as an age model constraint (upside-down triangles in Fig. 3c; see also the text below). All LPAZ-21P depths shallower than 63 cm are notably darker, changing from light to very dark brown over a depth interval of ≈2 cm. The onset of this change is constrained to be younger than 12 100±1100 yr BP (12.1±1.1 kyr BP) by a calibrated wood 14C age. There was a lack of suitable wood in LPAZ-21P in Holocene-aged sediments and our age models for this interval are constrained using U. peregrina 14C ages (circles in Fig. 3a) corrected for a modern reservoir age of 1240 years based on nearby seawater DIC 14C age observations at 600 m (Key et al., 2004) and converted to calendar ages using CALIB7.1 (Stuiver et al., 2017). These Holocene 14C ages are not tied to foraminifera abundance maxima and hence the Holocene calendar ages should be considered preliminary. The youngest calendar age for LPAZ-21P was 5.3 kyr BP, suggesting piston core over-penetration during sediment coring. Samples younger than the LPAZ-21P core top were obtained from the LPAZ-21PG core, whose age model was constrained identically to the Holocene-aged sediments of LPAZ-21P (see above). The Bayesian age model program BACON (Blaauw and Christen, 2011) was used to estimate the age and model error between the age model constraints.

The ET97-7T age model is constrained in three ways: using 14C ages of five pieces of microscopic wood from 18.9 to 15.3 kyr BP (diamonds in Fig. 3a and c); using U. peregrina 14C ages corrected for reservoir age in Holocene-aged sediment; and by synchronizing the apparently region-wide transition from light to dark-colored sediments (van Geen et al., 2003) to 12.1 kyr based on the wood-constrained age from LPAZ-21P (the X symbols in Fig. 3a and d). In lieu of reflectance data to quantify the brightness of the sediment cores, we present Ca∕Al estimated using X-ray fluorescence (see “Materials and methods” section below). The reasoning behind using Ca∕Al is that this metric (1) normalizes changes in terrestrial Ca input by dividing by Al and (2) is sensitive to the abundance of calcium carbonate microfossils. The sudden lowering of Ca∕Al at ≈65 cm in LPAZ-21P and ≈71 cm in ET97-7T is coincident with a decreased abundance of foraminifera and this presumably causes the darkening of these and other Holocene-aged sediments across the region. Ages between these constraints were estimated using BACON, as was done for the LPAZ-21P cores.

2.4 X-ray fluorescence

We estimated the Ca∕Al of LPAZ-21P and ET97-7T using an Avaatech XRF core scanner at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography Sediment Core Repository. The archived halves of the sediment cores were lightly scraped to expose less oxidized sedimentary material before analysis. More detailed methods (including software and signal processing) are identical to those previously described in Addison et al. (2013).

2.5 Wood 14C age test

Terrestrial plant life must have a younger 14C age and higher Δ14C than all contemporaneous foraminifera because of the air–sea difference in 14C content (e.g., see Fig. 1), and we used this inherent 14C age difference to check for contemporary deposition of the wood and microfossils in gulf sediments. Fourteen out of 20 microscopic wood fragment 14C ages passed the test and include one interval that may have been influenced by macrofauna consumption and excretion; it has a wood 14C age that is younger than foraminifera (see below).

One wood measurement that spectacularly failed this test presumably came from middle to late Holocene sediment (i.e., < 12 kyr BP aged sediments based on the depth below seafloor). However, this wood yielded a 14C age of > 25 kyr (see upside-down triangles in Fig. 3). We explain this remarkable 14C age difference as the erosion and deposition of relict wood stored on land before washing to the Gulf site during a rain event. The other wood measurements that failed this test gave 14C ages typically within measurement error or were ≈1000 14C years older than foraminifera 14C age. In total, 5 out of 20 wood 14C measurements were older than foraminifera in our sediment cores relative to 1 out of 26 wood 14C measurements by the only other study with a similar length age model (Zhao and Keigwin, 2018). This difference may be because the faster sedimentation rate of Zhao and Keigwin (2018) (20–60 cm kyr−1) leads to less bioturbation and a faster burial of the wood alongside foraminifera microfossils. Otherwise, the difference in rejections could be explained by our measurement of all wood, whereas Zhao and Keigwin (2018) only measured wood that still retained bark.

In light of this unusual application of calibrated 14C ages on wood in a marine setting, it is important to understand the potential errors. We assigned all calibrated wood ages a ±100 year uncertainty added in quadrature to the measurement and calibration error to account for possible lag in seafloor deposition. Note that the asymmetry of any errors associated with assuming contemporary growth of wood and foraminifera must be considered: if we underestimate the time from wood growth to sediment deposition, the actual calendar age of the sediment would be younger than the calendar age given in this study; hence, foram Δ14C values would be even lower than the large depletions shown here (see Eq. 1 and the Results section). Additionally, it is possible that a longer-than-expected time period between wood growth and sediment deposition could be “masked” by declining atmospheric 14C concentrations (Fig. 1), allowing the wood 14C age to pass our test for inclusion in the age model. These different histories for the wood found in our sediment cores would mean the calendar age is younger than we have assumed, thereby adjusting our benthic foraminifera Δ14C values to lower values than reported below. Given these potential influences on a wood 14C age-constrained age model, the uncertainty should primarily include the younger calendar age and not the ±100 year Gaussian uncertainty we assume. However, without a more exhaustive statistical study of age model errors when using wood, it is simpler and more conservative to utilize a Gaussian age model error.

Given these potential errors, it is worth considering the modern 14C age difference between seawater at the sediment–water interface and the atmosphere. A measurement of seawater DIC 14C age close to our core site and depth (at 22∘ N, 110∘ W at 598 m) gives a 14C age of 1240 yr BP. Assuming that DIC at this depth has not yet been seriously impacted by bomb 14C (Key et al., 2004) this would predict a pre-bomb wood-to-benthic foraminifera 14C age difference of 1240 yr BP. This is consistent with our data presented below, showing that the 14C age difference between concurrent wood and benthic foraminifera P. ariminensis and U. peregrina varies between this and even larger 14C age differences (Table 2).

3.1 Age model and sedimentation rates

The old core-top age for the LPAZ-21P core (5.3 kyr BP) indicates a poor recovery of the youngest sediments by the piston core, similar to nearby coring sites on the Pacific margin (van Geen et al., 2003). The LPAZ-21PG gravity core calendar ages range from 7954 to 504 yr BP, suggesting that it recovered much of the material missed by the piston core. Both cores give similar sedimentation rates of 16 to 18 cm kyr−1 over this Holocene interval (see Fig. 3a). The nearby trigger core ET97-7T gives a slightly lower sedimentation rate for this time interval (pink in Fig. 3), which may result from regional hydrographic differences, different seafloor dynamics, or sediment recovery based on different coring technology. Core recovery equipment may also explain differences in downcore sedimentation rates between the sites (5 cm kyr−1 versus 19 cm kyr−1 in ET97-7T during the 13 to 15 kyr BP interval; Fig. 3).

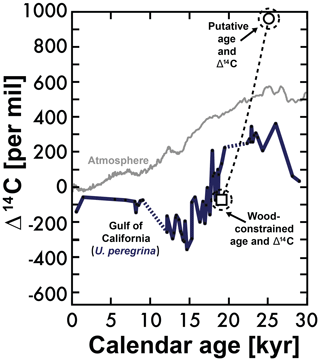

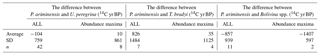

A wood 14C age-constrained age model has only been applied twice before (Broecker, 2004; Zhao and Keigwin, 2018), and it is worth quantifying the suitability of this approach in our cores. First, we applied a quantitative test: the wood 14C age must be older than all coexisting foraminifera 14C ages. This test included planktic foraminifera measurements that will be discussed in a forthcoming paper. The difference between benthic foraminifera and wood 14C ages is illustrative of the effectiveness of this test. The difference between the 14C age of benthic foraminifera (P. ariminensis and U. peregrina) and coexisting wood that passed our test is 2346±1599 years (n=14) and 2309±1063 years (n=13), respectively (Table 2). Only comparing wood with foraminifera abundance maxima gives a 14C age difference of 3353±1957 years (P. ariminensis; maximum of 5815 years, minimum of 1077 years, n=6) and 2697±1117 years (U. peregrina; maximum of 4145 years, minimum of 1480 years, n=6). These values are consistent with bottom water at our core sites that is near or older than the modern pre-bomb seawater–atmosphere 14C age difference of 1240 years (see above). Given these results, we argue that our test for excluding wood 14C ages is appropriate, but that unlikely circumstances may have existed that could hide the timescale of deposition. In the event of a longer-than-expected time between wood growth and deposition in the sediment, the calendar age would be biased to younger ages, making benthic foraminifera Δ14C values even more depleted than calculated (Fig. 5).

The excellent age model controls provided by wood 14C provide us with a powerful (and not always flattering) insight into the sedimentation rates of the Gulf cores. For example, our wood-constrained calendar ages identify two periods of slow sedimentation (or possibly hiatus events) in LPAZ-21P (between 22.7 and 19.5 kyr BP and between 12.1 and 9 kyr BP; see gray bars in Figs. 3, 4, and 6). The earlier interval is bracketed by wood-constrained calendar ages, while the shallower and/or more recent sedimentation rate slowdown begins approximately at the end of the Younger Dryas or less than ≈12.1 kyr BP.

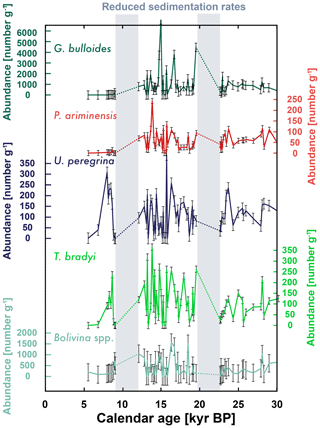

Figure 4Foraminifera abundance at site LPAZ-21P for planktic (G. bulloides) and benthic species (all others). Error bars represent 2 times the typical standard deviation for replicate counts.

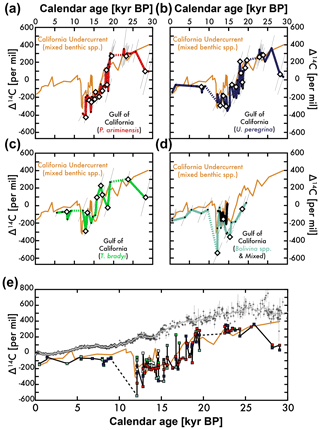

Figure 5The 14C isotopic composition (corrected for decay as Δ14C) for Gulf of California benthic foraminifera monospecies (a–d) and mixed species (d) compared with monospecies and mixed-species benthic foraminifera Δ14C measurements from the California Undercurrent sediment core site (orange) (Lindsay et al., 2015; Marchitto et al., 2007) over the past 30 000 yr BP. See core locations in Fig. 2. Canted error bars take into account measurement and age model errors (Stuiver et al., 2017). Diamonds indicate Δ14C at foraminifera abundance maximum. The Δ14C of all gulf benthic foraminifera (see Fig. 3 legend) is shown (e) alongside atmospheric Δ14C (gray) (Reimer et al., 2013) and California Undercurrent site Δ14C (orange). Modern Δ14C near the depth of the gulf and Pacific sites is about −173‰ (Key et al., 2004).

3.2 Foraminifera abundance estimates

The abundance of four benthic and one planktic foraminifera species in the LPAZ-21P core is highly variable with the abundance of planktic species G. bulloides as high as > 6000 g−1 of sediment (Fig. 4). The least abundant foraminifera was P. ariminensis, which had peak values just over 200 g−1. The abundance of G. bulloides and all other planktic foraminifera (not shown) in these sediments dropped sharply after 12.1 kyr BP – a loss of planktic foraminifera preservation that is also seen at the nearby California Undercurrent site (red diamond in Fig. 2) (Lindsay et al., 2015). The abundance of P. ariminensis also drops to zero after 12.9 kyr BP, while U. peregrina and T. bradyi decline to lower but persistent values ≈2 kyr later. Bolivina spp. are known to persist in low oxygen waters and are the most abundant foraminifera in LPAZ-21P and LPAZ-21PG sediments for the past 7 kyr.

Figure 6Comparing Gulf of California U. peregrina Δ14C with anomalous values based on the Bayesian calendar age (circle) based on sediment depth and the wood-constrained calendar age (square). If this anomaly was not the result of human error (mislabeling of the sample depth), then this may suggest the influence of macrofauna. See text for more details.

It is important to identify the abundance of sedimentary foraminifera when measuring 14C because the vertical mixing of sediment by macrofauna and microfauna (bioturbation) can grossly bias the 14C results (Keigwin and Guilderson, 2009), causing foraminifera 14C ages to be older on the shallow side of abundance peaks and vice versa. This effect was recently shown for Juan de Fuca Ridge sediments, where foraminifera 14C measurements shallower than a large abundance maxima were biased to “old” 14C ages (Costa et al., 2018). Below we explore the 14C age and Δ14C trends for each benthic foraminifera species.

3.3 Comparing benthic foraminifera 14C measurements

Examining the differences in the 14C age of the four benthic foraminifera species (Fig. 5), we find a maximum 5775-year offset between U. peregrina and T. bradyi 14C age (the former being older). Even though the sample sizes are small (7 to 42), comparing the preferred epifaunal P. ariminensis (Keigwin, 2002) to the other species suggests that (1) Bolivina spp. 14C age is older, (2) T. bradyi 14C age is younger, and (3) U. peregrina gives a 14C age that is most similar to the epifaunal species (Table 3; left side).

Table 3Comparison between benthic foraminifera 14C ages for all measurements (ALL) and only at abundance maxima (see Fig. 4).

The comparisons above, however, are likely influenced by bioturbation and a more appropriate examination would only compare the 14C ages of foraminifera at the abundance maxima, at which the influence of bioturbation is minimized (see above). One drawback to an abundance-maximum-only comparison is that it draws from a smaller pool of observations (e.g., n=2 for the P. ariminensis vs. Bolivina spp.), which limits the significance of these statistics. This abundance-only comparison suggests that on average U. peregrina (n=9) and T. bradyi (n=5) give similar 14C ages to epifaunal species, but with a large (10±861 years) to very large (35±1125 years) range of variability. On average, Bolivina spp. at abundance maxima (n=3) give an even older 14C age difference from the preferred epifaunal species (Table 3; right side).

Despite these 14C age differences, the glacial–deglacial trends of all four benthic foraminifera 14C (corrected for decay and shown as Δ14C in Fig. 5) from our cores near the mouth of the Gulf of California (the “Gulf” sediment core sites) are depleted relative to the atmosphere during the deglaciation, but are considerably higher during the Holocene. The shallowest and therefore most recent benthic foraminifera Δ14C are roughly equal to modern DIC Δ14C measurements of −173‰ at the depth of the cores (Key et al., 2004). Error bars denote 1 sigma calendar age and Δ14C errors and symbols represent measurements at abundance maxima. The 14C ages of foraminifera on either side of abundance peaks can also be “corrected” (Costa et al., 2018), although this requires an assumption about bioturbation rates, but this will be the subject of future work.

Each monospecies Δ14C record in Fig. 5a to d is compared with the nearby benthic foraminifera Δ14C record from the open Pacific margin of Baja California (a combination of mixed and monospecies benthic foraminifera on the original age model; see core locations in Fig. 2 and Table 1; Lindsay et al., 2015; Marchitto et al., 2007). Additionally, a series of mixed benthic Δ14C measurements (preliminary work on ET97-7T for which species abundance was not quantified) is shown in Fig. 5d. All Gulf benthic foraminifera Δ14C measurements are compiled in Fig. 5e (black) to illustrate the overall range of values given by the four benthic and mixed-species measurements relative to the atmospheric (gray; Reimer et al., 2013) and the undercurrent site Δ14C (orange). As can be seen by these multiple views of the dataset, all benthic foraminifera Δ14C trends at both Gulf and Undercurrent sites shift to lower values after 20 kyr BP. These depletions relative to atmospheric Δ14C are very large, but even lower Δ14C values are observed for intermediate-depth sediment core sites in the eastern equatorial Pacific (Stott et al., 2009).

3.4 Influence of macrofaunal consumption and excretion on sediment 14C ages?

In a single interval from 106 to 110 cm of the LPAZ-21P core, which was predicted to be ≈25.5 kyr based on interpolation from our Bayesian statistical age model, the wood and benthic and planktic foraminifera 14C ages were conspicuously younger than expected, giving a Δ14C value well above the contemporary atmosphere (956.3‰; see circle in Fig. 6). In fact, wood found within this sedimentary interval suggests a calendar age of only 19.2 kyr BP, giving a much lower U. peregrina Δ14C of −88.6‰. This lower Δ14C value is consistent with values for the wood-constrained calendar age (see square in Fig. 6). If these anomalous but self-consistent observations are not simply a result of human error (mislabeling or other sampling problem) they may indicate the presence in this interval of “zoophycos” or the remnants of downward-burrowing macrofauna (as was suggested by Lougheed et al., 2018). By consuming and later excreting sedimentary material, these worms are able to move “younger” sedimentary components deeper in the sediment column, though if this is the cause, the self-consistency of our 14C measurements in this reworked interval (in which microfossil and wood 14C ages suggest an undisturbed sample) is surprising.

Figure 7From top to bottom: atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) (blue; same as Fig. 1), atmospheric CO2 Δ14C (gray; same as Fig. 1), mixed and monospecies benthic foraminifera Δ14C from the California Undercurrent site (orange) (Lindsay et al., 2015; Marchitto et al., 2007), all monospecies benthic foraminifera Δ14C from near the mouth of the Gulf of California (black), sedimentation rate of LPAZ-21P (see Fig. 3), alongside benthic foraminifera P. ariminensis δ13C (pink) and δ18O (green) from this study and Herguera et al. (2010).

3.5 The stable isotopic composition of oxygen (δ18O) and carbon (δ13C)

The epifaunal benthic foraminifera (P. ariminensis) δ18O and δ13C measurements in Fig. 7 use new and published data from LPAZ-21P (Herguera et al., 2010), but on our wood-constrained age model. As previously reported, intermediate-depth δ13C shows little variability between the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) and Holocene at the depth of this core (624 m; Herguera et al., 2010). Benthic foraminifera δ18O has a similar magnitude of change to benthic δ18O for the nearby Undercurrent core sites (Fig. 7 in Lindsay et al., 2016), although the undercurrent benthic δ18O increase to Holocene values may lag the gulf site values (compare Lindsay et al., 2016 with Fig. 7).

Based on the work presented here, the trend towards an extreme lowering of intermediate-depth benthic foraminifera Δ14C in the northeastern Pacific (the California Undercurrent site in Figs. 1, 2, and 5) (Lindsay et al., 2015; Marchitto et al., 2007) cannot be explained by species biases, bioturbation, or poor age model controls (Fig. 5). This statement is supported by our 14C measurements of the epifaunal benthic foraminifera P. ariminensis – a species known to provide the best record of seawater carbon at the sediment–water interface (Keigwin, 2002) – and several commonly used infaunal benthic foraminifera from sediment cores “upstream” of the canonical record of these extreme Δ14C observations (Figs. 1 and 5). Our measurements indicate that even though the potential variability between infaunal and the preferred epifaunal species 14C ages is relatively large (several hundred years; Table 3), the average 14C age difference at foraminifera abundance maxima is < 100 years, and the overall trend towards extremely low Δ14C during the deglaciation cannot be explained by bioturbation and persists regardless of species.

4.1 Comparing gulf and undercurrent site deglacial records

Our Gulf sediment core observations indicate that the mixed-species Δ14C measurements from the Undercurrent sites shown in Figs. 1 and 5 are largely accurate, although the higher values that form the middle of this “W-shaped” anomaly (from ≈15 to 13 kyr BP) are not obviously reproduced by any of the four monospecies benthic foraminifera Δ14C. It is possible that this and some other smaller-scale features of a mixed benthic Δ14C record reflect the bias of a particular species and/or the influence of bioturbation in our lower sedimentation rate sites. For example, the benthic foraminifera T. bradyi is a possible suspect for biasing mixed benthic Δ14C measurements because it is relatively large, dense, and sometimes has large deviations to younger 14C ages than the other species (Fig. 5). Nevertheless, the overall agreement between the independently derived Undercurrent and Gulf records lends credence to the methods used to construct the age model by Marchitto et al. (2007) and tested by Lindsay et al. (2016). We should note that we cannot explain the large offset between the records from 30 to 25 kyr BP, although this comparison only includes one observation from the Undercurrent sites.

The similar Δ14C trends at both sites despite sedimentation rate differences and sediment core hiatus lend additional support to the robustness of the Δ14C trends (Lindsay et al., 2016) and against events such as the large-scale – and far-fetched – redeposition of sand-sized sedimentary components. In principle, the circulation of bottom waters from the Gulf to the Undercurrent sediment core sites could allow for redeposition of benthic foraminifera with much older 14C ages, but a much larger reworked component (and hence much older benthic foraminifera 14C ages) would logically be expected at the “upstream” Gulf sites. In fact, sedimentary redeposition should be amplified at the lower-sedimentation-rate Gulf site, but significantly lower benthic foraminifera Δ14C is not observed for any of the species at the Gulf sites.

These findings allow us to now focus our questions on two potential explanations for the extreme depletions of benthic foraminifera Δ14C observed during the deglaciation: (1) it is a diagenetic signal imparted onto both epifaunal and infaunal foraminifera after burial or (2) it reflects a real change in seawater Δ14C during the deglaciation.

4.2 Can diagenesis explain the low deglacial Δ14C?

Investigating the potential for diagenetic alteration of benthic foraminifera Δ14C, we are not concerned about the newly observed coupling between carbonate dissolution and precipitation (Subhas et al., 2017), which only involves a few monolayers of surface carbonate. Instead, producing the extreme Δ14C lowering observed at Undercurrent and Gulf sites (Fig. 5) and other sites around the globe (Bryan et al., 2010; Stott et al., 2009; Thornalley et al., 2011) requires the precipitation of depleted 14C on or within the foraminifera test.

This authigenic calcium carbonate formation and foraminifera 14C content has been examined in several ways. For example, benthic foraminifera from the eastern equatorial Pacific give some of the lowest observed deglacial Δ14C values (−609‰), but scanning electron microscope images show no authigenic carbonate on benthic or planktic foraminifera (Stott et al., 2009). Calcium carbonate overgrowth (via the conversion of CaCO3 to CaSO4 or gypsum) was observed in Santa Barbara Basin sediments (Magana et al., 2010), but would not influence the 14C content of the microfossil. What's more, extreme 14C depletions of mixed benthic foraminifera from this and other sites were found to be biased by Pyrgo spp., which are inexplicably depleted in 14C (Ezat et al., 2017). Other work suggests younger-than-expected 14C ages from the precipitation of carbonate onto foraminifera tests after core recovery (Skinner et al., 2010). Cook et al. (2011) observed that anomalously low foraminifera Δ14C, high δ18O, and low δ13C was consistent with authigenic carbonate precipitation from methane. Wycech et al. (2016) also compared the 14C ages of translucent and opaque monospecific planktic foraminifera from the same sediment horizons and found that the opaque foraminifera (thought to contain authigenic carbonate) had 14C ages more than 10 000 years older than the translucent tests.

Neither the Gulf nor the Undercurrent site benthic foraminifera measurements display the telltale signs of simultaneous Δ14C, δ18O, and δ13C anomalies seen by Cook et al. (2011) (see Fig. 7). What's more, the planktic Δ14C values from the Undercurrent site do not show anomalous depletion during the deglaciation (Lindsay et al., 2015), which is expected for postdepositional alteration and/or authigenic carbonate formation. It is also possible that a completely different process of authigenic carbonate formation is occurring in the subtropical eastern Pacific, but we cannot elaborate on what this mechanism might be. It is possible that authigenic carbonates are removed from the foraminiferal test during the 10 % acid leaching pretreatment at KCCAMS (see “Materials and methods” section), although selected pretreatment tests did not significantly alter the 14C ages. This pretreatment was not used in the Wycech et al. (2016) comparisons, but will be examined in our future studies.

Finally, given the near identical deglacial Δ14C trends at the Undercurrent and Gulf sites despite very different sedimentation rates (20–30 cm kyr−1 at the undercurrent versus 1 to 5 cm kyr−1 at the Gulf; Fig. 3) it would be surprising if the same depleted Δ14C trends were of diagenetic origin. This is because a faster sedimentation rate will decrease the potential for authigenic mineralization by decreasing the exposure time of the foraminifera. This reduction in exposure time would apply to both the microfossil's exposure at the sediment–water interface and at sediment depths favorable to authigenic carbonate precipitation. Thus, while the potential influence of authigenic carbonate on the primary foraminifera record is an important area of research that deserves further study, the similarity of the Undercurrent and Gulf records argues against contamination from authigenic carbonate precipitation as the major influence on these benthic foraminifera Δ14C values.

If the extreme deglacial depletion of benthic foraminifera Δ14C at these northeastern Pacific sites cannot be explained by species or habitat bias, bioturbation, or poor age model control, the remaining explanation is that they reflect a change in seawater DIC Δ14C. Looking to other proxy systems, deep-sea coral Δ14C in the North Atlantic and Southern Ocean – archives with excellent age model control and different diagenetic influences – also display depleted Δ14C during the deglaciation (Adkins et al., 1998; Burke and Robinson, 2012; Chen et al., 2015; Robinson et al., 2005). However, the deep-sea coral Δ14C depletions have a different timing and are not as extreme as observed for the Gulf of California and California Undercurrent sites (Fig. 5e).

A leading candidate among the potential explanations for these and other intermediate-depth records (Bryan et al., 2010) is the deep-sea sequestration and flushing of carbon through the intermediate-depth ocean (Basak et al., 2010; Du et al., 2018; Lindsay et al., 2016; Marchitto et al., 2007). This interpretation is plausibly consistent with 14C records from only a few sites, such as the deep Southern Ocean (Barker et al., 2010; Skinner et al., 2010) and deep Nordic Seas (Thornalley et al., 2015). However, using an 18-box geochemical ocean–atmosphere model to simulate glacial–interglacial ocean circulation and carbon cycling, Hain et al. (2011) argue that matching the observed Δ14C depletions in the intermediate-depth Northern Hemisphere sites requires unrealistic changes in ocean chemistry (e.g., lower surface ocean alkalinity) and ocean dynamics (i.e., mixing). Specifically, to appropriately “age” deep-sea 14C requires deep-sea anoxia, which is not observed. Furthermore, the release of this deep-sea 14C to intermediate depths would dissipate much quicker than the several-thousand-year anomaly shown in Fig. 5e.

An alternative explanation involves the addition of 14C-depleted carbon via mid-ocean ridge (MOR) volcanism (Ronge et al., 2016), which is indirectly supported by evidence of increased MOR activity (Lund, 2013; Middleton et al., 2016; Tolstoy, 2015). The locations and depths of the extreme benthic foraminifera Δ14C lowering are also suggestive of a MOR influence given their proximity to the East Pacific Rise–Gulf of California (Marchitto et al., 2007; Ronge et al., 2016; Stott et al., 2009; this study), the Red Sea (Bryan et al., 2010), and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (Thornalley et al., 2011). However, this hypothesis of enhanced carbon flux from seafloor volcanism must also explain the many intermediate-depth sites that do not show anomalous deglacial Δ14C depletions (Broecker and Clark, 2010; Cléroux et al., 2011; De Pol-Holz et al., 2010). Furthermore, this proposed carbon addition must have been associated with an alkalinity addition, without which the increased seawater CO2 concentrations and therefore lower seawater pH would have caused a global-scale carbonate dissolution event (Lindsay et al., 2016; Stott and Timmermann, 2011).

In summary, our work strongly suggests that at least for the Gulf of California and adjacent Pacific sites, the foraminifera Δ14C proxy records real 14C changes in deglacial intermediate-depth seawater DIC, but the question of what caused those changes remains open. Careful examination to confirm or disprove the fidelity of the benthic foraminifera Δ14C on a case-by-case basis will be a critical part of building a reliable body of data to identify the controls on glacial–interglacial marine carbon cycling.

The radiocarbon data can be accessed at these locations: NOAA https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/25650 (NOAA, 2018) and PANGAEA https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.896312 (Rafter et al., 2018).

All authors contributed to the text, sample preparation, and sample analysis.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We thank Chanda Bertrand, Alexandra Hangsterfer (SIO Core Repository),

Hector Martinez, Nassib Shammas, Mariam Ayad, Megha Rudresh, Alyssa De la

Rosa, Juan Troncoso, Julian DeLine, Jazmin Sanchez, Chassidy Manlapid, and

Matthew Chan.

Edited by: Luke

Skinner

Reviewed by: Tom Marchitto and two anonymous referees

Addison, J. A., Finney, B. P., Jaeger, J. M., Stoner, J. S., Norris, R. D., and Hangsterfer, A.: Integrating satellite observations and modern climate measurements with the recent sedimentary record: An example from Southeast Alaska: Modern SE Alaska Fjord Sediment Records, J. Geophys. Res.-Ocean., 118, 3444–3461, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20243, 2013.

Adkins, J. F., Cheng, H., Boyle, E. A., Druffel, E. R. M., and Edwards, L. R.: Deep-Sea Coral Evidence for Rapid Change in Ventilation of the Deep North Atlantic 15,400 Years Ago, Science, 280, 725–728, 1998.

Ahn, J. and Brook, E. J.: Siple Dome ice reveals two modes of millennial CO2 change during the last ice age, Nat. Commun., 5, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4723, 2014.

Barker, S., Knorr, G., Vautravers, M. J., Diz, P., and Skinner, L. C.: Extreme deepening of the Atlantic overturning circulation during deglaciation, Nat. Geosci., 3, 567–571, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo921, 2010.

Basak, C., Martin, E. E., Horikawa, K., and Marchitto, T. M.: Southern Ocean source of 14C-depleted carbon in the North Pacific Ocean during the last deglaciation, Nat. Geosci., 3, 770–773, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo987, 2010.

Blaauw, M. and Christen, J. A.: Flexible paleoclimate age-depth models using an autoregressive gamma process, Bayesian Anal., 6, 457–474, 2011.

Broecker, W. S.: Glacial to interglacial changes in ocean chemistry, Prog. Oceanogr., 11, 151–197, 1982.

Broecker, W. S.: Ventilation of the Glacial Deep Pacific Ocean, Science, 306, 1169–1172, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1102293, 2004.

Broecker, W. S. and Clark, E.: Search for a glacial-age 14C-depleted ocean reservoir, Geophys. Res. Lett., 37, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010GL043969, 2010.

Broecker, W. S., Klas, M., Ragano-Beavan, N., Mathieu, G., and Mix, A.: Accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon measurements on marine carbonate samples from deep sea cores and sediment traps, Radiocarbon, 30, 35, 261–295, 1988.

Bryan, S. P., Marchitto, T. M., and Lehman, S. J.: The release of 14C-depleted carbon from the deep ocean during the last deglaciation: Evidence from the Arabian Sea, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 298, 244–254, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2010.08.025, 2010.

Burke, A. and Robinson, L.: The Southern Ocean's Role in Carbon Exchange During the Last Deglaciation, Science, 335, 557–561, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1215110, 2012.

Chen, T., Robinson, L. F., Burke, A., Southon, J., Spooner, P., Morris, P. J., and Ng, H. C.: Synchronous centennial abrupt events in the ocean and atmosphere during the last deglaciation, Science, 349, 1537–1541, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac6159, 2015.

Cléroux, C., deMenocal, P., and Guilderson, T.: Deglacial radiocarbon history of tropical Atlantic thermocline waters: absence of CO2 reservoir purging signal, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 30, 1875–1882, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.04.015, 2011.

Cook, M. S., Keigwin, L. D., Birgel, D., and Hinrichs, K.-U.: Repeated pulses of vertical methane flux recorded in glacial sediments from the southeast Bering Sea, Paleoceanography, 26, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010PA001993, 2011.

Costa, K. M., McManus, J. F., and Anderson, R. F.: Radiocarbon and Stable Isotope Evidence for Changes in Sediment Mixing in the North Pacific over the Past 30 kyr, Radiocarbon, 60, 113–135, https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2017.91, 2018.

De Pol-Holz, R., Keigwin, L., Southon, J., Hebbeln, D., and Mohtadi, M.: No signature of abyssal carbon in intermediate waters off Chile during deglaciation, Nat. Geosci., 3, 192–195, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo745, 2010.

Du, J., Haley, B. A., Mix, A. C., Walczak, M. H., and Praetorius, S. K.: Flushing of the deep Pacific Ocean and the deglacial rise of atmospheric CO2 concentrations, Nat. Geosci., 11, 749–755, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0205-6, 2018.

Ezat, M. M., Rasmussen, T. L., Thornalley, D. J. R., Olsen, J., Skinner, L. C., Hönisch, B., and Groeneveld, J.: Ventilation history of Nordic Seas overflows during the last (de)glacial period revealed by species-specific benthic foraminiferal 14C dates, Paleoceanography, 32, 172–181, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016PA003053, 2017.

Field, D. B.: Variability in vertical distributions of planktonic foraminifera in the California Current: Relationships to vertical ocean structure, Paleoceanography, 19, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003PA000970, 2004.

Galbraith, E. D., Jaccard, S. L., Pedersen, T. F., Sigman, D. M., Haug, G. H., Cook, M., Southon, J. R., and Francois, R.: Carbon dioxide release from the North Pacific abyss during the last deglaciation, Nature, 449, 890–893, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06227, 2007.

Gómez-Valdivia, F., Parés-Sierra, A., and Flores-Morales, A. L.: The Mexican Coastal Current: A subsurface seasonal bridge that connects the tropical and subtropical Northeastern Pacific, Cont. Shelf Res., 110, 100–107, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csr.2015.10.010, 2015.

Hain, M. P., Sigman, D. M., and Haug, G. H.: Shortcomings of the isolated abyssal reservoir model for deglacial radiocarbon changes in the mid-depth Indo-Pacific Ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010gl046158, 2011.

Herguera, J. C., Herbert, T., Kashgarian, M., and Charles, C.: Intermediate and deep water mass distribution in the Pacific during the Last Glacial Maximum inferred from oxygen and carbon stable isotopes, Quaternary Sci. Rev., 29, 1228–1245, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.02.009, 2010.

Jaccard, S. L. and Galbraith, E. D.: Large climate-driven changes of oceanic oxygen concentrations during the last deglaciation, Nat. Geosci., 5, 151–156, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo1352, 2011.

Jaccard, S. L., Galbraith, E. D., Martínez-García, A., and Anderson, R. F.: Covariation of deep Southern Ocean oxygenation and atmospheric CO2 through the last ice age, Nature, 530, 207–210, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16514, 2016.

Keeling, C. D.: The concentration and isotopic abundances of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, Tellus, 12, 1–4, 1960.

Keigwin, L. D.: Late Pleistocene-Holocene paleoceanography and ventilation of the Gulf of California, J. Oceanogr., 58, 421–432, 2002.

Keigwin, L. D. and Guilderson, T. P.: Bioturbation artifacts in zero-age sediments, Paleoceanography, 24, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008PA001727, 2009.

Keigwin, L. D. and Lehman, S. J.: Radiocarbon evidence for a possible abyssal front near 3.1 km in the glacial equatorial Pacific Ocean, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 425, 93–104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.05.025, 2015.

Key, R. M., Kozyr, A., Sabine, C. L., Lee, K., Wanninkhof, R., Bullister, J. L., Feely, R. A., Millero, F. J., Mordy, C., and Peng, T. H.: A global ocean carbon climatology: Results from Global Data Analysis Project (GLODAP), Global Biogeochem. Cy., 18, 1–23, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004gb002247, 2004.

Lindsay, C. M., Lehman, S. J., Marchitto, T. M., and Ortiz, J. D.: The surface expression of radiocarbon anomalies near Baja California during deglaciation, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 422, 67–74, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.04.012, 2015.

Lindsay, C. M., Lehman, S. J., Marchitto, T. M., Carriquiry, J. D., and Ortiz, J. D.: New constraints on deglacial marine radiocarbon anomalies from a depth transect near Baja California, Paleoceanography, 31, 1103–1116, https://doi.org/10.1002/2015PA002878, 2016.

Lougheed, B. C., Metcalfe, B., Ninnemann, U. S., and Wacker, L.: Moving beyond the age-depth model paradigm in deep-sea palaeoclimate archives: dual radiocarbon and stable isotope analysis on single foraminifera, Clim. Past, 14, 515–526, https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-14-515-2018, 2018.

Lund, D. C.: Deep Pacific ventilation ages during the last deglaciation: Evaluating the influence of diffusive mixing and source region reservoir age, Earth Planet. Sc. Lett., 381, 52–62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2013.08.032, 2013.

MacFarling Meure, C., Etheridge, D., Trudinger, C., Steele, P., Langenfelds, R., van Ommen, T., Smith, A., and Elkins, J.: Law Dome CO2, CH4 and N2O ice core records extended to 2000 years BP, Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006GL026152, 2006.

Magana, A. L., Southon, J. R., Kennett, J. P., Roark, E. B., Sarnthein, M., and Stott, L. D.: Resolving the cause of large differences between deglacial benthic foraminifera radiocarbon measurements in Santa Barbara Basin, Paleoceanography, 25, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1029/2010PA002011, 2010.

Marchitto, T. M., Lehman, S. J., Ortiz, J. D., Fluckiger, J., and van Geen, A.: Marine Radiocarbon Evidence for the Mechanism of Deglacial Atmospheric CO2 Rise, Science, 316, 1456–1459, 2007.

Marcott, S. A. and Shakun, J. D.: A record of ice sheet demise, Science, 358, 721–722, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaq1179, 2017.

Middleton, J. L., Langmuir, C. H., Mukhopadhyay, S., McManus, J. F., and Mitrovica, J. X.: Hydrothermal iron flux variability following rapid sea level changes, Geophys. Res. Lett., 43, 3848–3856, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL068408, 2016.

Monnin, E.: Atmospheric CO2 Concentrations over the Last Glacial Termination, Science, 291, 112–114, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.291.5501.112, 2001.

NOAA: Gulf of California Foraminifera and Wood 14C Data, https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/paleo-search/study/ 25650, last access: 12 December 2018.

Petit, J. R., Jouzel, J., Raynaud, D., Barkov, N. I., Barnola, J. M., Basile, I., Bender, M., Chappellaz, J., Davis, M., Delaygue, G., Delmotte, M., Kotlyakov, V. M., Legrand, M., Lipenkov, V. Y., Lorius, C., Pepin, L., Ritz, C., Saltzman, E., and Stievenard, M.: Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica, Nature, 399, 429–436, 1999.

Rafter, P. A., Herguera, J. C., Southon, J. R.: Foraminifera and wood 14C (radiocarbon) in Northeast Pacific for past 30,000 years, PANGAEA, available at: https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.896312, last access: 12 December 2018.

Reimer, P., Bard, E., Bayliss, A., Beck, J., Blackwell, P., Bronk, R., Buck, C., Cheng, H., Edwards, R., Friedrich, M., Grootes, P., Guilderson, T., Haflidason, H., Hajdas, I., Hatte, C., Heaton, T., Hoffmann, D., Hogg, A., Hughen, K., Kaiser, K., Kromer, B., Manning, S., Niu, M., Reimer, R., Richards, D., Scott, E., Southon, J., Staff, R., Turney, C., and van der Plicht, J.: IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves 0–50,000 years cal BP, Radiocarbon, 55, 1869–1887, 2013.

Roach, L. D., Charles, C. D., Field, D. B., and Guilderson, T. P.: Foraminiferal radiocarbon record of northeast Pacific decadal subsurface variability, J. Geophys. Res.-Ocean., 118, 4317–4333, https://doi.org/10.1002/jgrc.20274, 2013.

Robinson, L. F., Adkins, J. F., Keigwin, L. D., Southon, J., Fernandez, D. P., Wang, S.-L., and Scheirer, D. S.: Radiocarbon Variability in the Western North Atlantic During the Last Deglaciation, Science, 310, 1469–1473, 2005.

Ronge, T. A., Tiedemann, R., Lamy, F., Köhler, P., Alloway, B. V., De Pol-Holz, R., Pahnke, K., Southon, J., and Wacker, L.: Radiocarbon constraints on the extent and evolution of the South Pacific glacial carbon pool, Nat. Commun., 7, 11487, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms11487, 2016.

Rose, K. A., Sikes, E. L., Guilderson, T. P., Shane, P., Hill, T. M., Zahn, R., and Spero, H. J.: Upper-ocean-to-atmosphere radiocarbon offsets imply fast deglacial carbon dioxide release, Nature, 466, 1093–1097, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09288, 2010.

Santos, G. M., Moore, R. B., Southon, J. R., Griffin, S., Hinger, E., and Zhang, D.: AMS 14C sample preparation at the KCCAMS/UCI Facility: status report and performance of small samples, Radiocarbon, 49, 255–270, 2007.

Sikes, E. L., Samson, C. R., Guilderson, T. P., and Howard, W. R.: Old radiocarbon ages in the southwest Pacific Ocean during the last glacial period and deglaciation, Nature, 405, 555–559, 2000.

Skinner, L. C., Fallon, S., Waelbroeck, C., Michel, E., and Barker, S.: Ventilation of the Deep Southern Ocean and Deglacial CO2 Rise, Science, 328, 1147–1151, 2010.

Southon, J., Santos, G., Druffel-Rodriguez, K., Druffel, E., Trumbore, S., Xu, X., Griffin, S., Ali, S., and Mazon, M.: The Keck Carbon Cycle AMS laboratory, University of California, Irvine: initial operation and a background surprise, Radiocarbon, 46, 41–49, 2004.

Stott, L. and Timmermann, A.: Hypothesized Link Between Glacial/Interglacial Atmospheric CO2 Cycles and Storage/Release of CO2-Rich Fluids From Deep-Sea Sediments, in: Geophysical Monograph Series, vol. 193, edited by: Rashid, H., Polyak, L., and Mosley-Thompson, E., American Geophysical Union, Washington, DC, 123–138, 2011.

Stott, L., Southon, J., Timmermann, A., and Koutavas, A.: Radiocarbon age anomaly at intermediate water depth in the Pacific Ocean during the last deglaciation, Paleoceanography, 24, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008PA001690, 2009.

Stuiver, M. and Polach, H. A.: Discussion; reporting of C-14 data., Radiocarbon, 19, 355–363, 1977.

Stuiver, M., Reimer, P., and Reimer, R.: CALIB 7.1, available from: http://www.calib.org, last access: 2 January 2017.

Subhas, A. V., Adkins, J. F., Rollins, N. E., Naviaux, J., Erez, J., and Berelson, W. M.: Catalysis and chemical mechanisms of calcite dissolution in seawater, P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 114, 8175–8180, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1703604114, 2017.

Thornalley, D. J. R., Barker, S., Broecker, W. S., Elderfield, H., and McCave, I. N.: The Deglacial Evolution of North Atlantic Deep Convection, Science, 331, 202–205, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1196812, 2011.

Thornalley, D. J. R., Bauch, H. A., Gebbie, G., Guo, W., Ziegler, M., Bernasconi, S. M., Barker, S., Skinner, L. C., and Yu, J.: A warm and poorly ventilated deep Arctic Mediterranean during the last glacial period, Science, 349, 706–710, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa9554, 2015.

Tolstoy, M.: Mid-ocean ridge eruptions as a climate valve, Geophys. Res. Lett., 42, 1346–1351, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GL063015, 2015.

van Geen, A., Zheng, Y., Bernhard, J. M., Cannariato, K. G., Carriquiry, J., Dean, W. E., Eakins, B. W., Ortiz, J. D., and Pike, J.: On the preservation of laminated sediments along the western margin of North America, Paleoceanography, 18, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003pa000911, 2003.

Voelker, A. H. L., Sarnthein, M., Grootes, P. M., Erlenkeuser, H., Laj, C., Mazaud, A., Nadeau, M.-J., and Schleicher, M.: Correlation of Marine 14C Ages from the Nordic Seas with the GISP2 Isotope Record: Implications for 14C Calibration Beyond 25 ka BP, Radiocarbon, 40, 517–534, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033822200018397, 1998.

Wycech, J., Kelly, D. C., and Marcott, S.: Effects of seafloor diagenesis on planktic foraminiferal radiocarbon ages, Geology, 44, 551–554, https://doi.org/10.1130/G37864.1, 2016.

Zhao, N. and Keigwin, L. D.: An atmospheric chronology for the glacial-deglacial Eastern Equatorial Pacific, Nat. Commun., 9, 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05574-x, 2018.